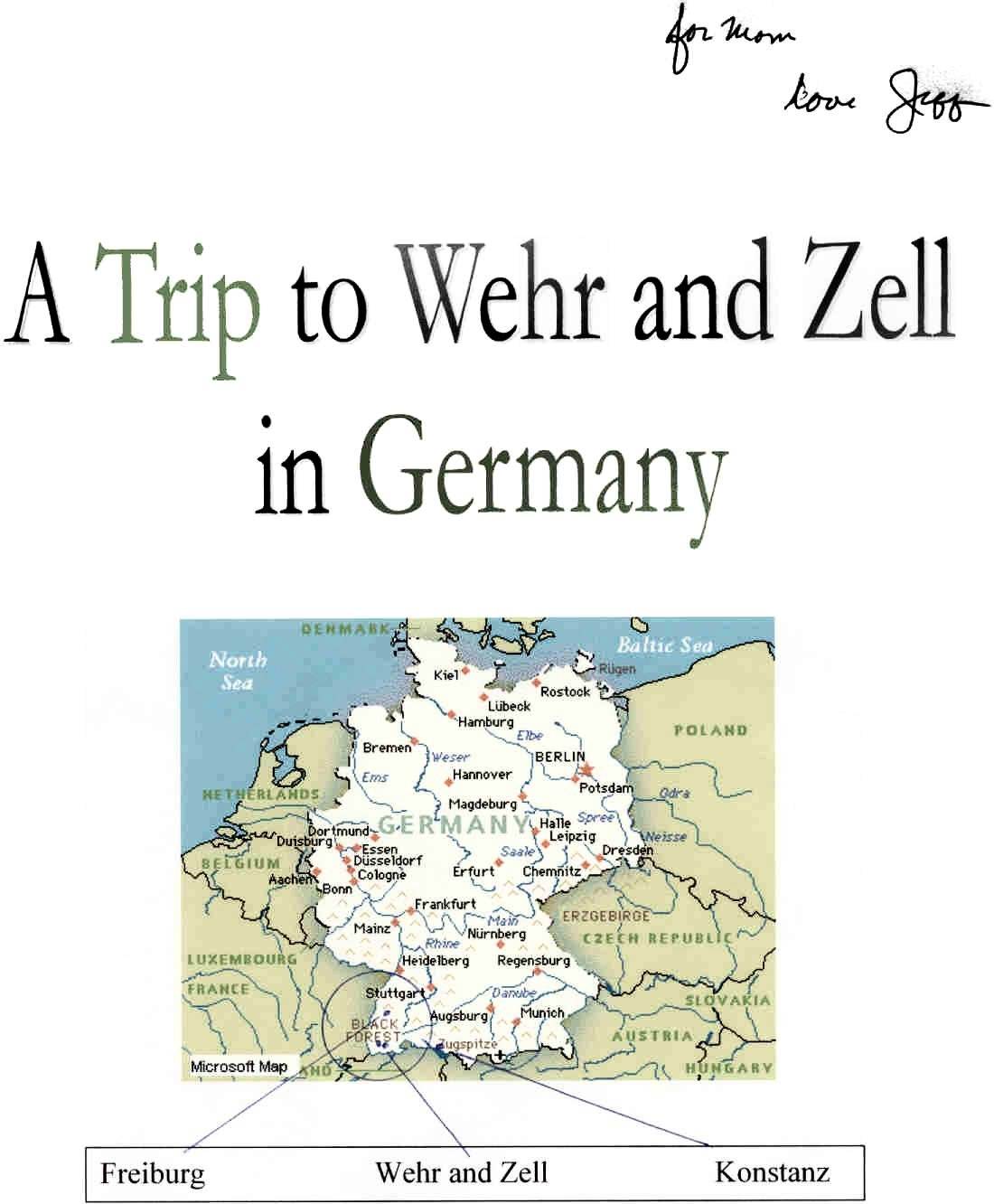

Jeff Meyer's report to his mother Elsa Trefzger Meyer.

2003

Scroll down to read the entire account.

"Back to the Roots" A Trip to Wehr and Zell

Although I spent only two days in Wehr and Zell, it was the real purpose

of my week-long trip to Germany--to see the small towns where the

Trefzger and Berger families originated, over 150 years ago. I am not

completely sure why I wanted to do this. I think that I wanted to find

out, if by going there I could feel some connection with the past, re-

experience it in some way. I thought that I might see something in a

face that was reminiscent of a Berger or Trefzger that I knew, and

actually feel some sense of what had been, a long time ago. None of this

happened, but I am still glad that I went, if only to get these ancestral

shadows out of my mind.

On an Waterbed in Wehr

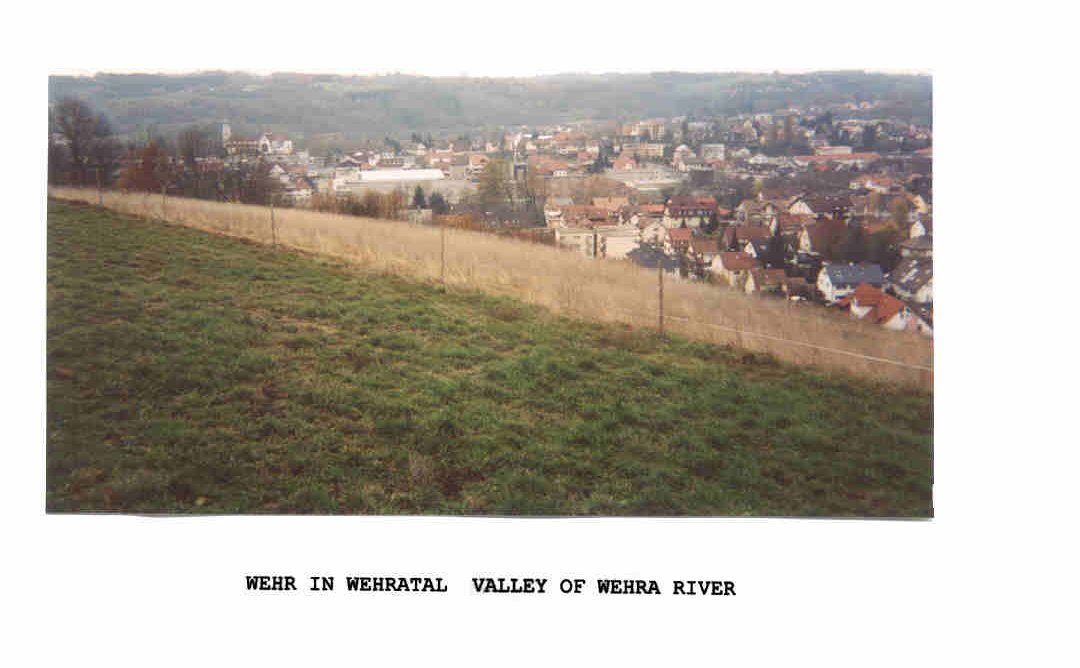

But back to my trip to Wehr and Zell. I got from Freiburg to Wehr by

train and bus. The last 10 kilometers by bus was a pleasant drive

between Schopfheim where I got off the train, and Wehr. The country

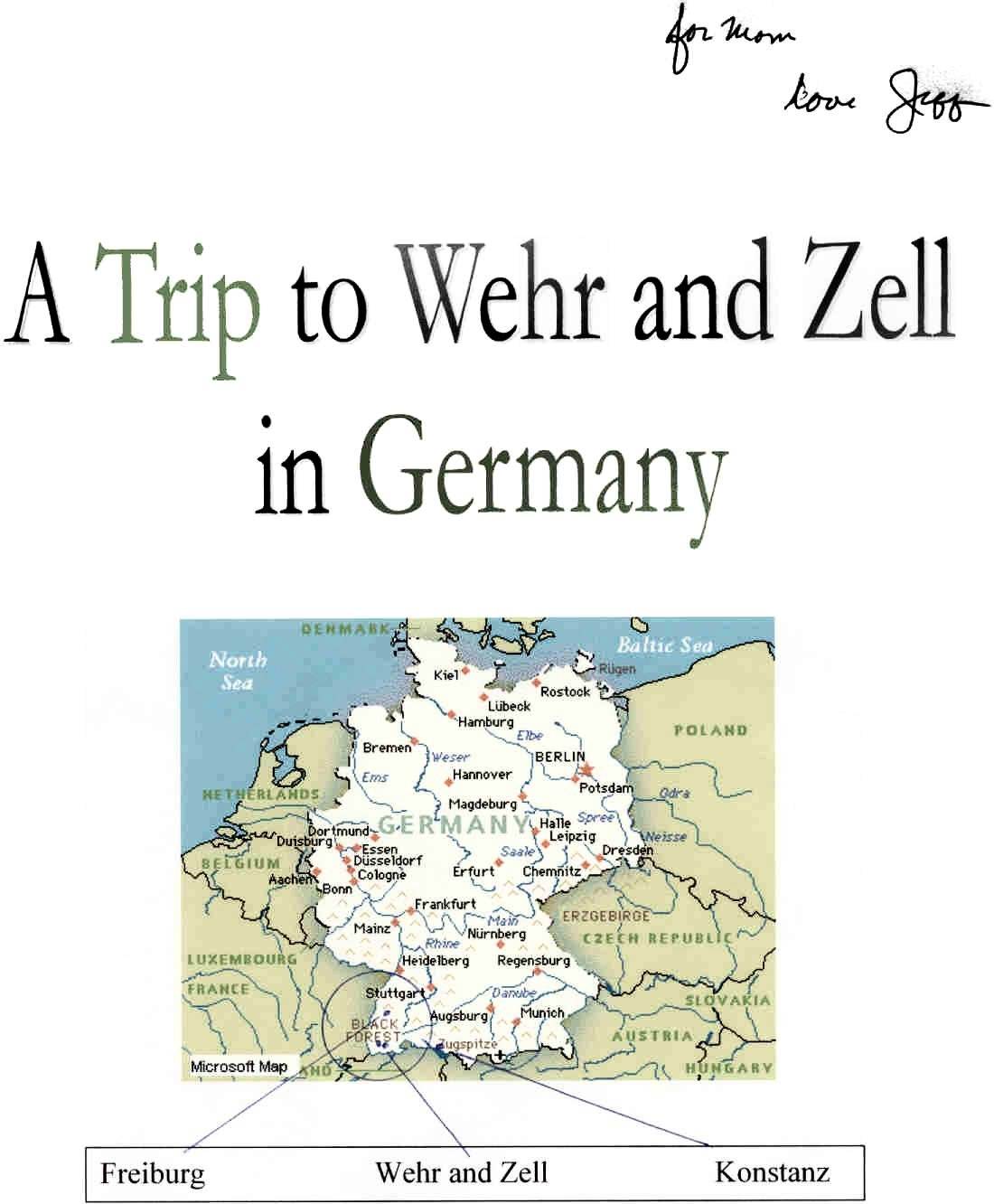

reminded me of parts of the Blue Ridge Parkway. Wehr is in a valley at

the southern end of the Black Forest Mountains, rolling fields and lots of

woods, pine and hardwoods deep into their late fall colors. I think the

area reminded me of the Blue Ridge Parkway also because there is no

advertising to deface the countryside.

I had found nothing about Webr in my travel guide, so while in Freiburg

I looked through some other travel guides, in a bookstore. Only one had

mentioned it, with a single notice of a hotel called the Klosterhof. For

this I was grateful, because when I arrived at 3:00pm the tourist

information center had already closed. So I walked about a half mile to

the northern edge of town, found the place but it had a sign on the door

"ruhiger tag" which meant that they were closed for a "rest" day. So

reluctantly, I turned around and headed back to the town center, by this

time having a bad case of overfull bladder. Where do you go to pee in a

small town? Finally, in fair agony, I spotted a bar that was open, bolted

through the door and asked the barman "where's the toilet?" He looked

at me grumpily and motioned to a door in back. Happiness, as Snoopy

might say, is finding a john when you need one!

When I came out I felt obliged to buy a beer, and I explained to him in

my seriously limited German why I had come to Wehr. "Ja, Ja," he said

"we have lots of Trefzgers and Bergers," obviously unimpressed with

my quest. I checked out the local telephone listIngs and found 41

Trefzgers in Wehr and 24 Bergers. For Zell, which is smaller, there

were 24 Bergers and 8 Trefzgers. On the wall of his establishment was

an enlargement of a photo about 100 years ago. I would have

to say that, compared to the rather tidy and prosperous town I had

found today, this old Wehr looked run down, with shambly buildings

and muddy streets. When I asked him if he knew a place I might stay

for the night, he said "keine ahnung" (no idea). Then another customer

arrived who was friendly and tried to help, but his local dialect was so

thick that I couldn't understand what he was talking about. I

remembered Grosspapa at Christmas time singing first "Oh

Tenenbaum," then singing it all over again in the Wehr area dialect. It

sounded something like "Oh Tanabooem. " So I left the tavern, and not

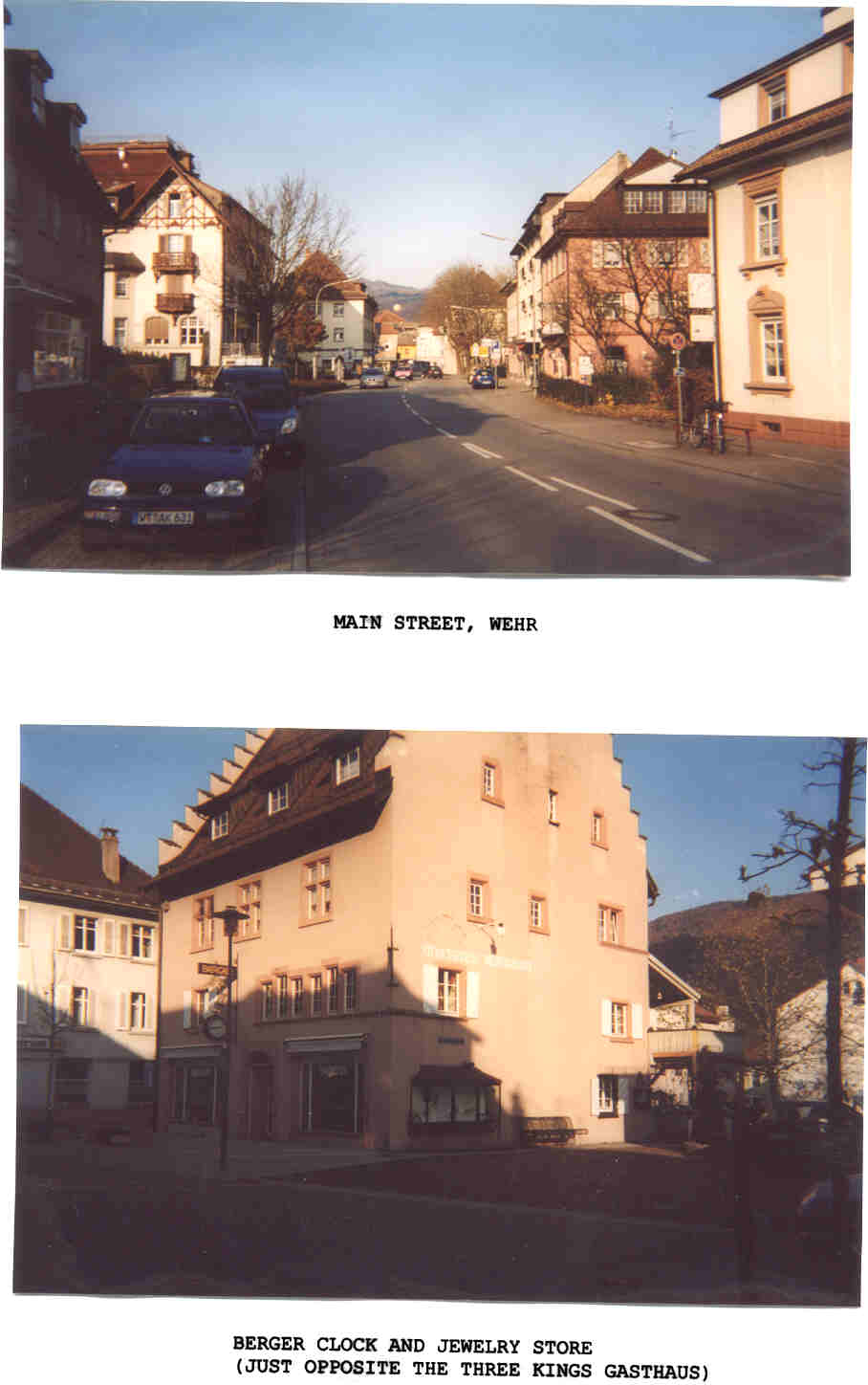

one block south saw a gasthaus/tavern on the corner called Three

Kings. Jerk. How could the barman not known about this place? This

one had customers and as I walked in everybody looked at me. Who is

this? I asked the bartender if they had a room available. He hesitated

but finally said that he thought they might have one, but I should please

come back after 6:00 pm.

So I wandered around a while and soon the obligatory beer was having

its effect, so I went into Michelangelo's Italian Restaurant to use the

facilities and stayed for an early dinner. I decided to switch to a small

glass of red wine this time. Who knows how long I'd be tramping

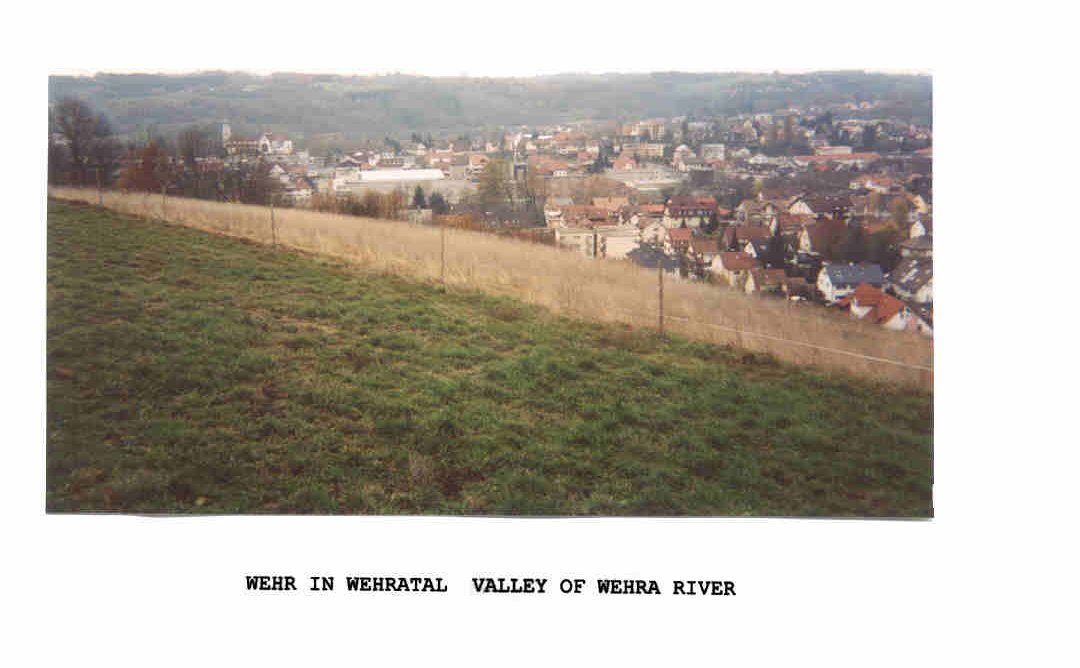

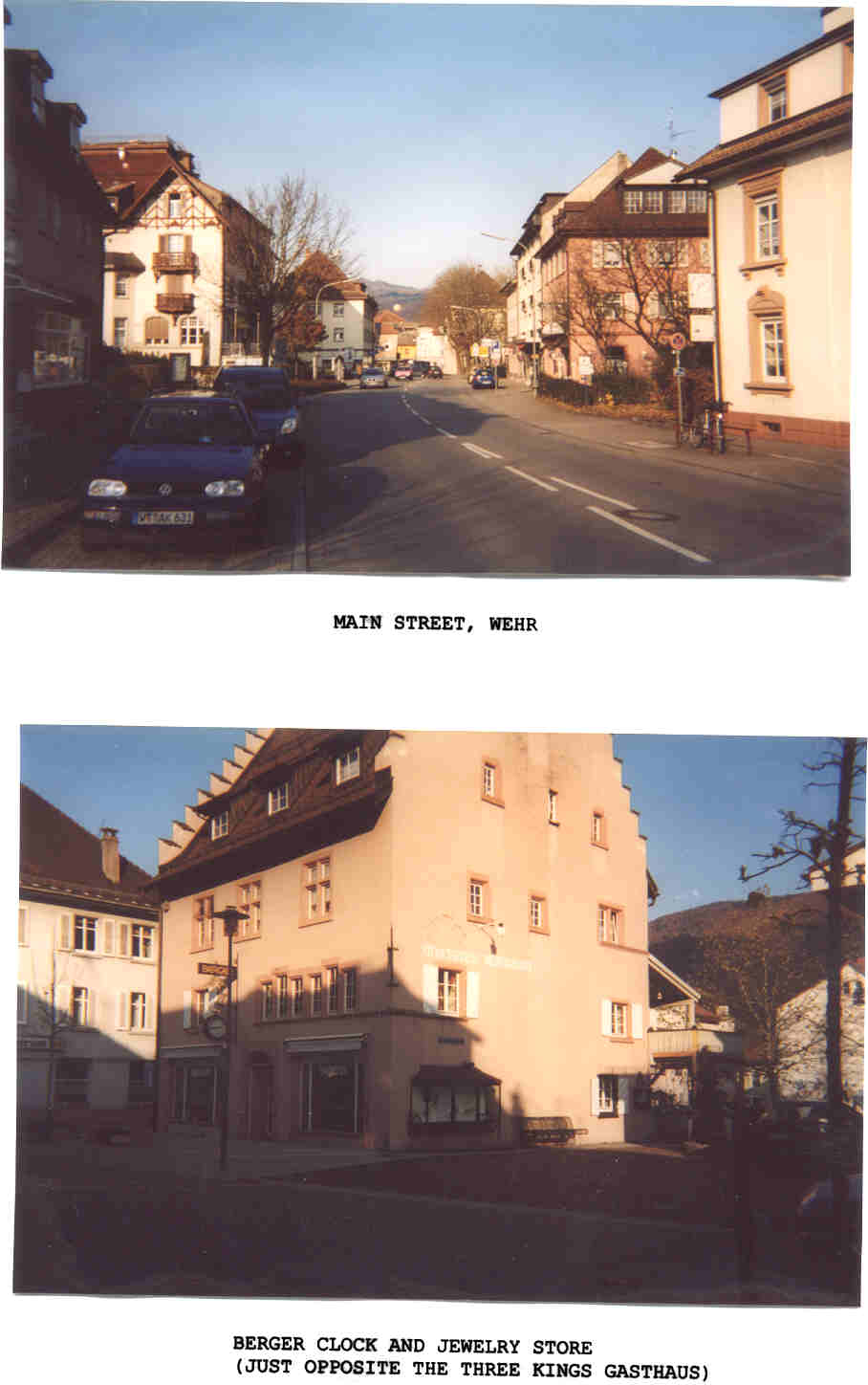

around after dinner? In my ramblings I had seen three or four shop signs

with Trefzger or Berger on them. I also had to readjust my concept of

Wehr. I suppose for me Wehr was supposed to be a little town in a

remote area that history had passed by. I remember Grosspapa talking a

lot about Wehr, so it had taken on a kind of mythic quality through my

remembering these grandfatherly accounts so long ago. Well, the news

is that Wehr has changed just like the rest of the world. All the high tech

shops are here, modular phones, computers, internet, video games and

all the rest. No old fellows wandering around in lederhosen, nor women

in Bavarian peasant style outfits. Chic boutiques, Italian and French

designer clothes, kids with piercings and metal rings, rock music, and

quite a few ethnic groups that I'm sure my great grandparents had never

seen: Turkish, Greek, south Asians, east Asians, and my hosts at

Michelanglo' s, from south of the Alps. One photography shop on Main

Street, along with the usual wedding and baby photos on the front

windows, had a photo of an entirely naked woman! Wehr is ahead of

Charlotte in that department.

After finishing my spagetti bolognese, heavy on pasta, light on sauce, I

returned to the Three Kings. They said yes, they could let me have a

room, if I could sleep on a waterbed. 27.50 Euros per night, breakfast

included. At this point, I was desperate, so I said I would be glad to try

the waterbed. The bar tender asked a blond woman to take me to my

room. She spoke perfect English (and so did he, I found out the next

day), from Texas. She pointed to her last Texas license plate, nailed to

the wall behind the bar. Next to it was a Maine license plate. That's my

brother's, she said, without any further explanation. The room was

huge, about 15 by 25 feet, though a bit threadbare. But at least I had a

place to stay. The wind was really roaring outside, coming right through

the cracks in the old windows. I worried that it might blow the window

boxes and their plastic flowers down onto the sidewalk below. I was on

the third floor, the water closet at the end of the corridor, the shower

downstairs on the second floor. "You've got 37 channels on that TV,"

said the blond woman, as though I had just won the lottery. After she

left, I pressed the remote and it fell apart. I tried the button on the TV

set. It didn't work. Oh well, who needs TV? I could look out my

window, and above the stores across the street, above the mountains was

a full moon. I wrote my journal entry that night wobbling on my water

cushion. Later that night I did get some "entertainment." Someone came

in about 3:00 and soon two people were yelling and arguing at the tops

of their voices. But I was so tired that it just became background noise.

I sailed off in my waterbed to the land of nod.

Next morning I went down to the bar and the bar tender asked if I

wanted breakfast. Yes, I said (of course, I thought, it was part of the

deal). I explained what I was doing in Wehr. He, too, was unimpressed,

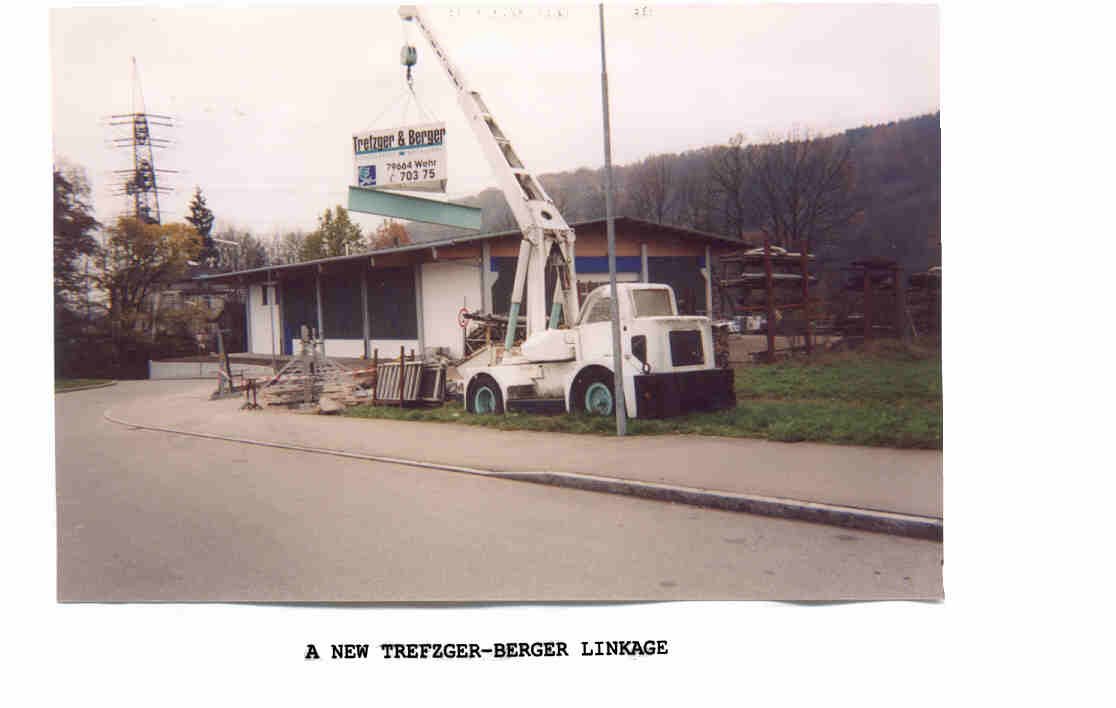

assuring me that Wehr had lots of Trefzgers and Bergers. There's a new

metal working company co-owned by a Trefzger and Berger, he said,

but they are not related. Old Trefzger, the co-owner's father, might be

in later. (He never came.) The blond appeared, in a funk. "I'm beat,"

she said to the bar tender, who I must be her husband. "I've

put on a ton of make up and it won't cover the black under my eyes." I

decided it was best not to inquire about last night's argument.

From the Three Kings I walked down a street that crossed the Wehra

river under a covered wooden bridge, and followed a path up the hillside

to the ruins of a fortress. First built in 1099 and variously rebuilt, the

last time in 1790, making it a fitting and secure place for the nobility of

Baden to live in when they visited the area. In other words, it housed the

nobles our ancestors left Wehr to get away from. Nothing was done

between 1790 and almost 1990 and then the Black Forest Verein (some

kind of heritage preservation group?) built a wooden viewing platform

above it. I climbed up to it and from there I could look across to the

town and saw the parish church of St. Martin, set on a hill and

architecturally dominating Wehr. I headed there next.

I found the church very busy preparing for the feast of St. Martin, which

was the next day, Sunday. Inside I discovered that the church was

restored to its baroque splendor, with three tromp l'oeil paintings on the

ceiling, leading you to think you are looking through a hole into the sky

where you can see Mary and the saints, and lots of cherubs. There was a

group of children up in the sanctuary and a director of some sort was

trying to explain their roles, I assumed, on the following day. They were

gabbing among themselves, and the director frequently banged his book

on the communion railing to get their attention.

Outside, I explored the graveyards, which pretty much surrounded the

church. Graveyards are extremely important in German Catholicism, I

discovered, far more so than in the U.S. Almost all the old gravestones

have been removed and replaced by new opulent ensembles of polished

granite or marble. They are beautifully landscaped with bushes, vines

and flowers, and carefully tended. Most of this has been done in the last

15 years or so, as Germany has become more affluent. I'm guessing, but

these grave ensembles must cost thousands of dollars to erect. So

different than in the U.S., the land of fading plastic flowers, renewed, if

the departed are lucky, once every few years. As I walked around I

counted some 8-10 people working on their family graves. One of these

was a woman tending a Trefzger grave (of which there were 10 to 15 by

my rough count). I asked her if she was a Trefzger. She said yes, on my

mother's side. I introduced myself as a Trefzger, which led to a brief

conversation about our families, brief because my German is so limited

and she spoke no English. But I could tell that she, too, was not

particularly impressed that I was a Trefzger - there are just so many of

them around. Maybe it would be like a German coming to the U.S.,

meeting a Mr. Schmidt and then saying, "Oh, I'm a Schmidt too." Not a

real conversation starter.

What I did find moving was a memorial to men from St. Martin's parish

who had died in World War 1 and World War 11. There were hundreds

of names listed.

I found, dead or missing in World War 1. six Trefzgers:

Alois

August

Theodor

Emil

Franz

Julius

Franz Trefzger. ...It was the name that got to me.

There were two Bergers:

Adolph

Johann Fridolin

Again, it was the name. John Berger.

In World War 11 there were nine Trefzgers:

Ernst

Gustav

Hermann (2)

Karl Friedrich

Sigfried

Otto

Walter

Wolfgang

And five Bergers:

Ernst

Franz Joseph

Max

otto

Wolfgang

I thought of how familiar, somehow, these names sounded, and how

different things could have been had our ancestors, with the same names,

not left for America, and how ordinary people get caught up in politics,

the military and war.

Threatened by Royalty in Zell

It was now late morning and time to leave for Zell im Wiesental.

Whenever I mentioned going to Zell, Germans would always ask "im

Wiesental?" So there must be one or more towns called Zell in

Germany. I returned to Schopfheim and took the train three more stops

to the last stop on the line, which was Zell. Zell is more remote and

picturesque than Wehr, far up the Wiesental valley, nestled in a place

where the river valley becomes narrow. The town is built on the

hillsides and the higher mountains tower above it. Still, if I was

expecting the place to have escaped the modern world, I was soon

disabused of that notion. The fIrst person I saw standing on the platform

as my train pulled in was what Julia would call "a goth" - modern, not

the old kind of goth. He was tall and thin, entirely clothed in black, his

leather covered with silver studs, bosses and chains. His head was

shaved except for a long pony tail. Like Wehr, Zell has changed with

time.

The town was somnolent on a Saturday afternoon with few stores

at all and fewer still open. There was a small fountain erected in honor

of Carl Maria von Weber and a street named after him, so I supposed

that he is Zell's most famous son. I checked an biographical dictionary

of musicians, and it did not list him as being born there. But he was the

cousin of Constanze, Mozart's wife, who was born there. That should

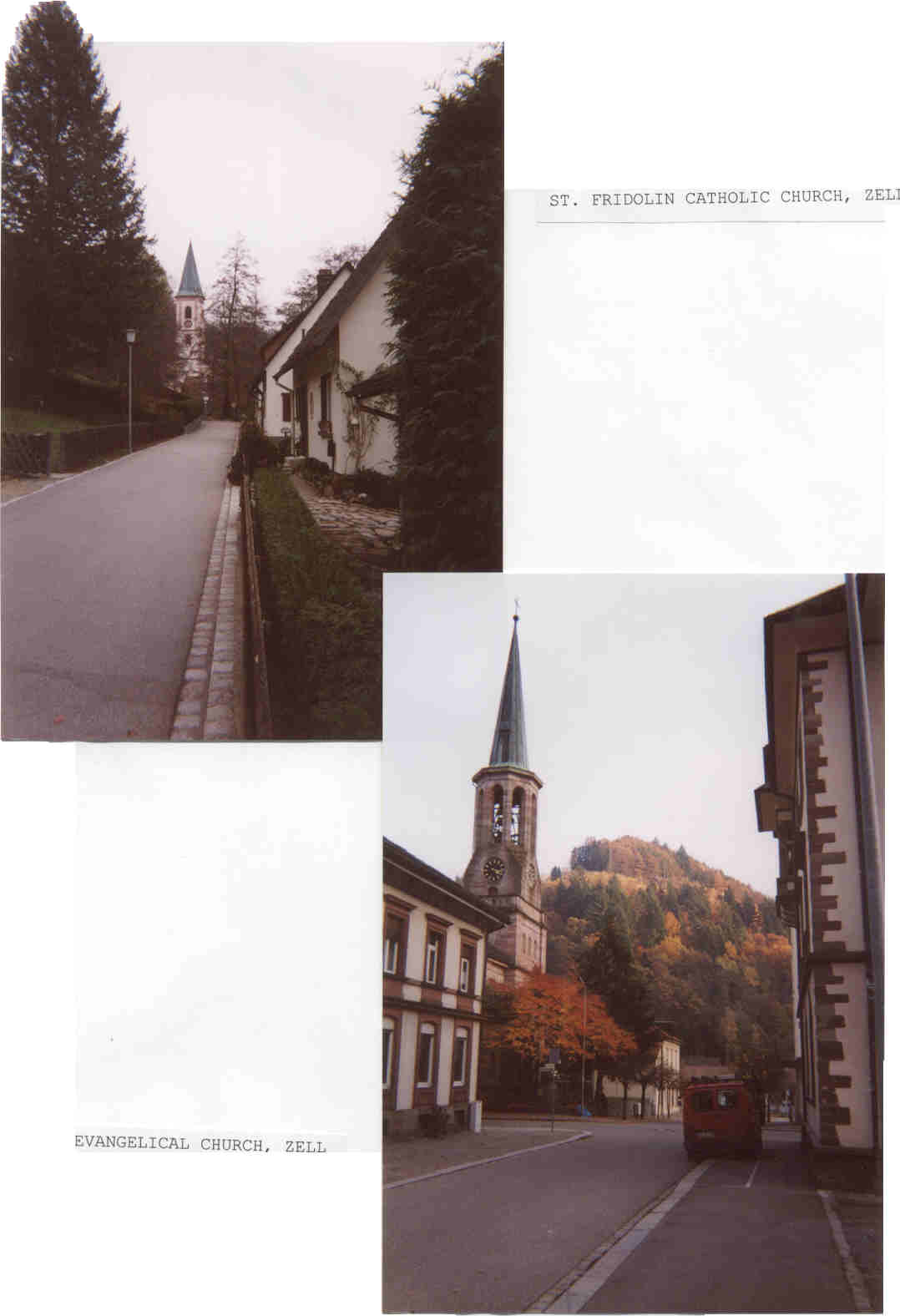

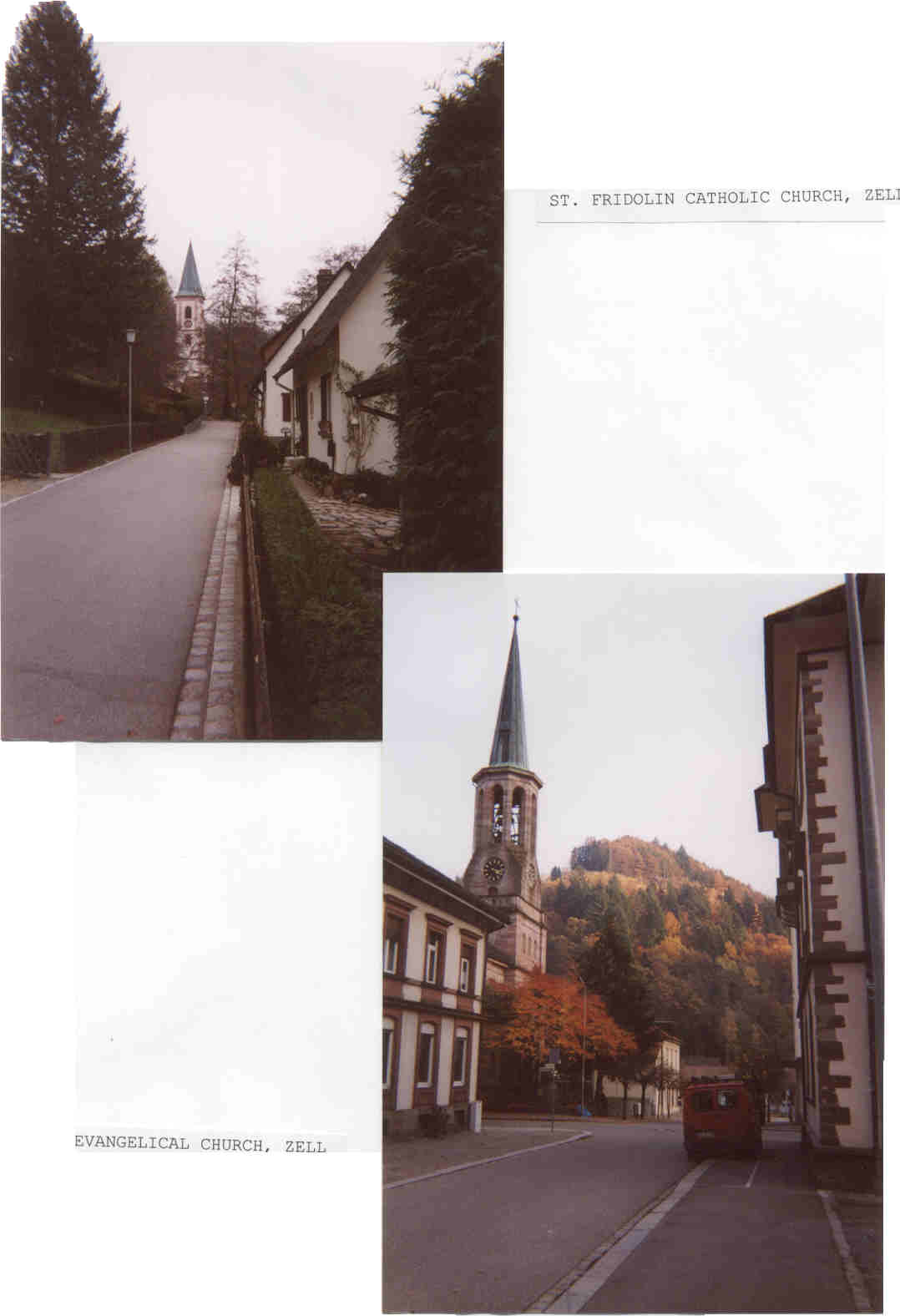

be fame enough. I walked up the hill to St. Fridolin Catholic Church.

Opposite it was a woodsy area with a long pond. I noticed a swan at the

upper end. As soon as he saw me he came roaring down the pond,

wings wildly flaping and hooting, coming to a screeching halt where the

pond ended just in front of me. I reached into my pack, broke off a

piece of bread and threw it to him. He glanced at it contemptuously and

continued to glare at me. I could see he was motived by royal

arrogance, not hunger and decided to leave him to his kingdom. I

walked across the street to the church.

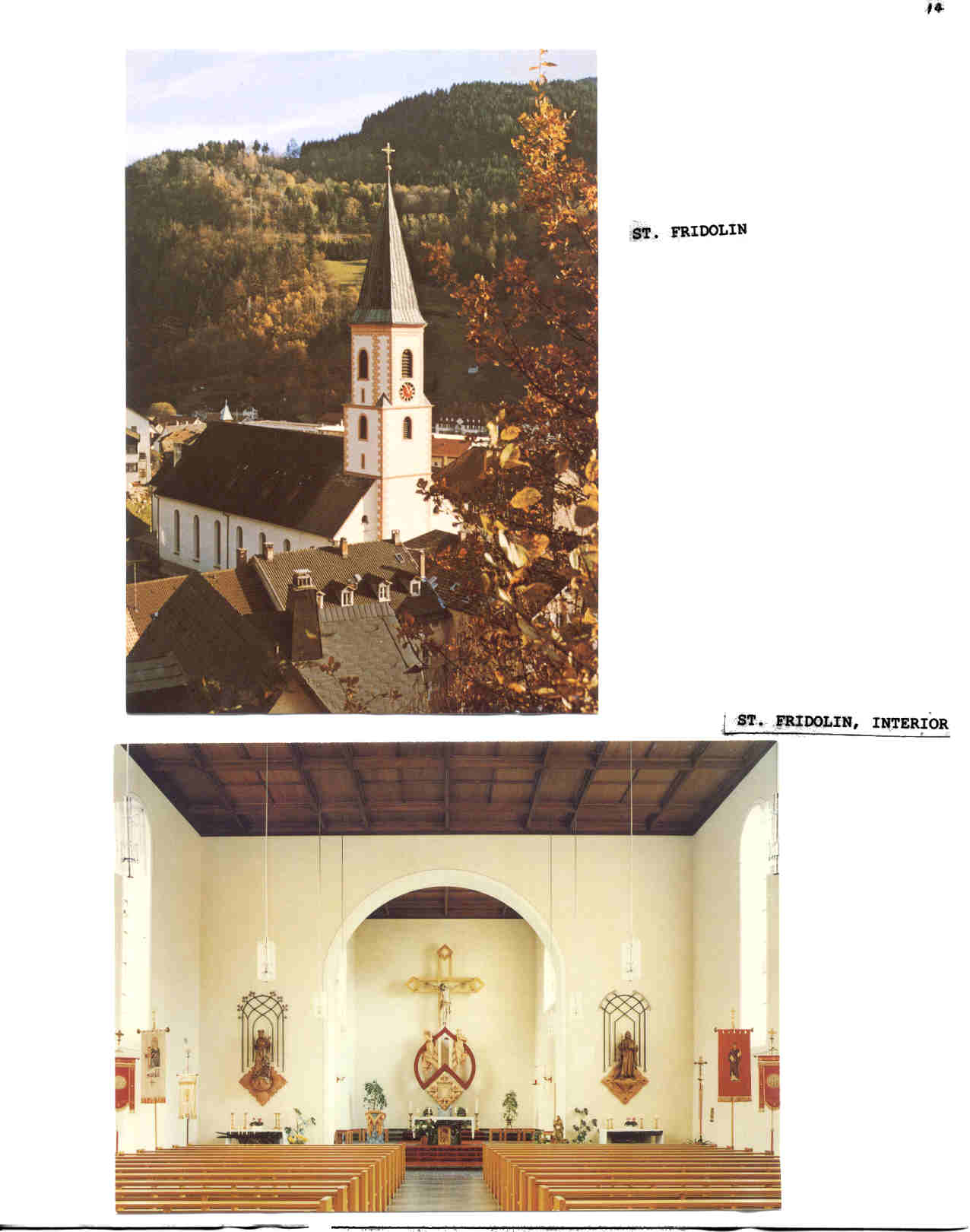

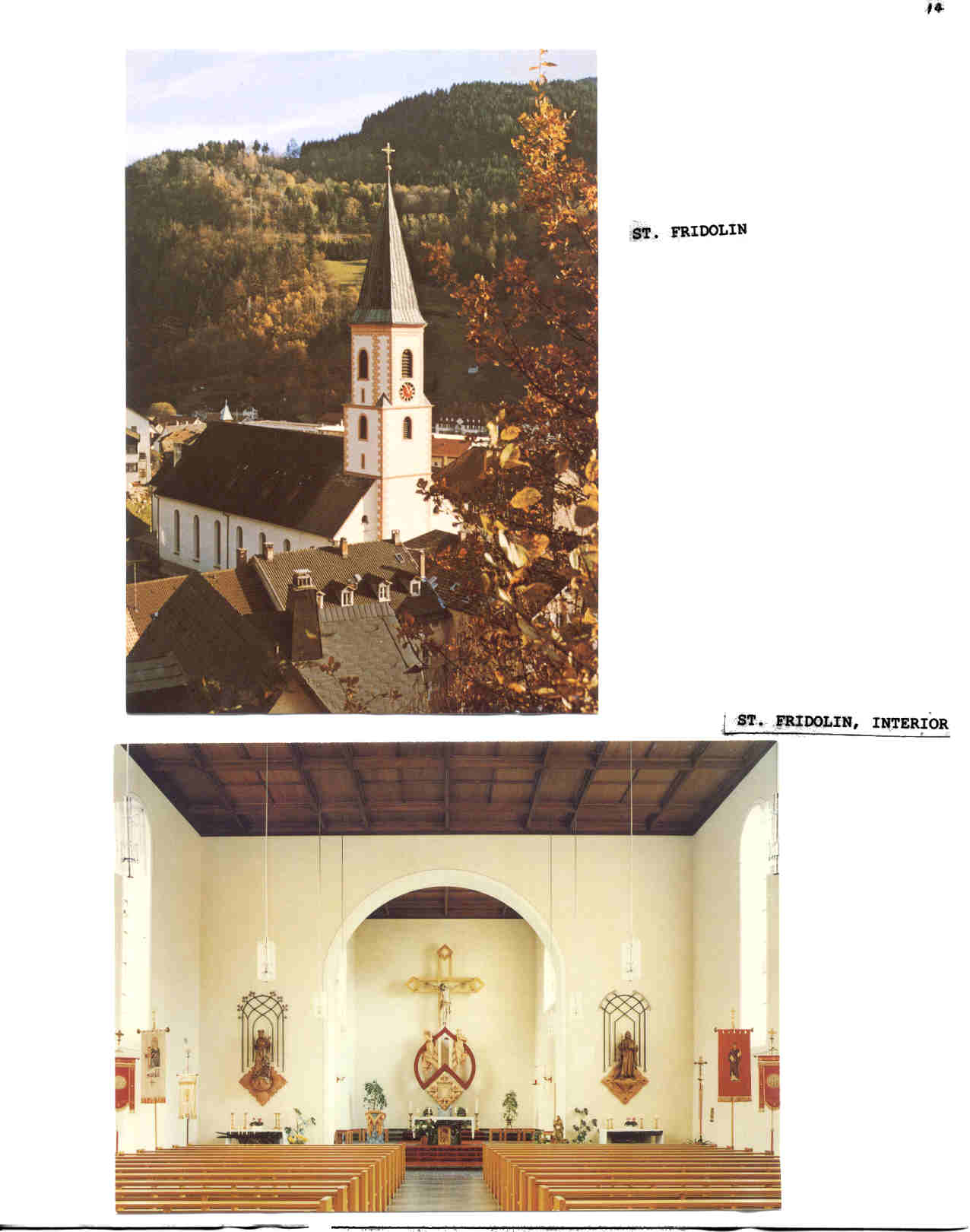

St. Fridolin was built in 1826 and would have been there for a few

decades when my great great grandfather Meinrad was getting ready to

leave Zell. I thought of the strong faith of the Bergers and Trefzgers that

must have been nourished in these two churches, St. Martins in Wehr

and St. Fridolin in Zell. Alfred, Richard, Adela, Herbert were the most

overtly religious, others perhaps less obviously so, but the Catholic

Church exerted a huge influence over all their lives and the lives of their

children. This strong religious influence in the families began in these

remote valleys in Baden over 150 years ago, nourished by these

churches. The inside of St. Fridolin was also in good condition, recently

refurbished and renovated but in a very different way from St. Martin.

The interior is now very contemporary in feeling, stripped down, simple,

austere. Clearly the much of the exuberance of design and the kitsch of

Catholic piety , statues, altars, decoration, was eliminated here, while it

was preserved at St. Martin.

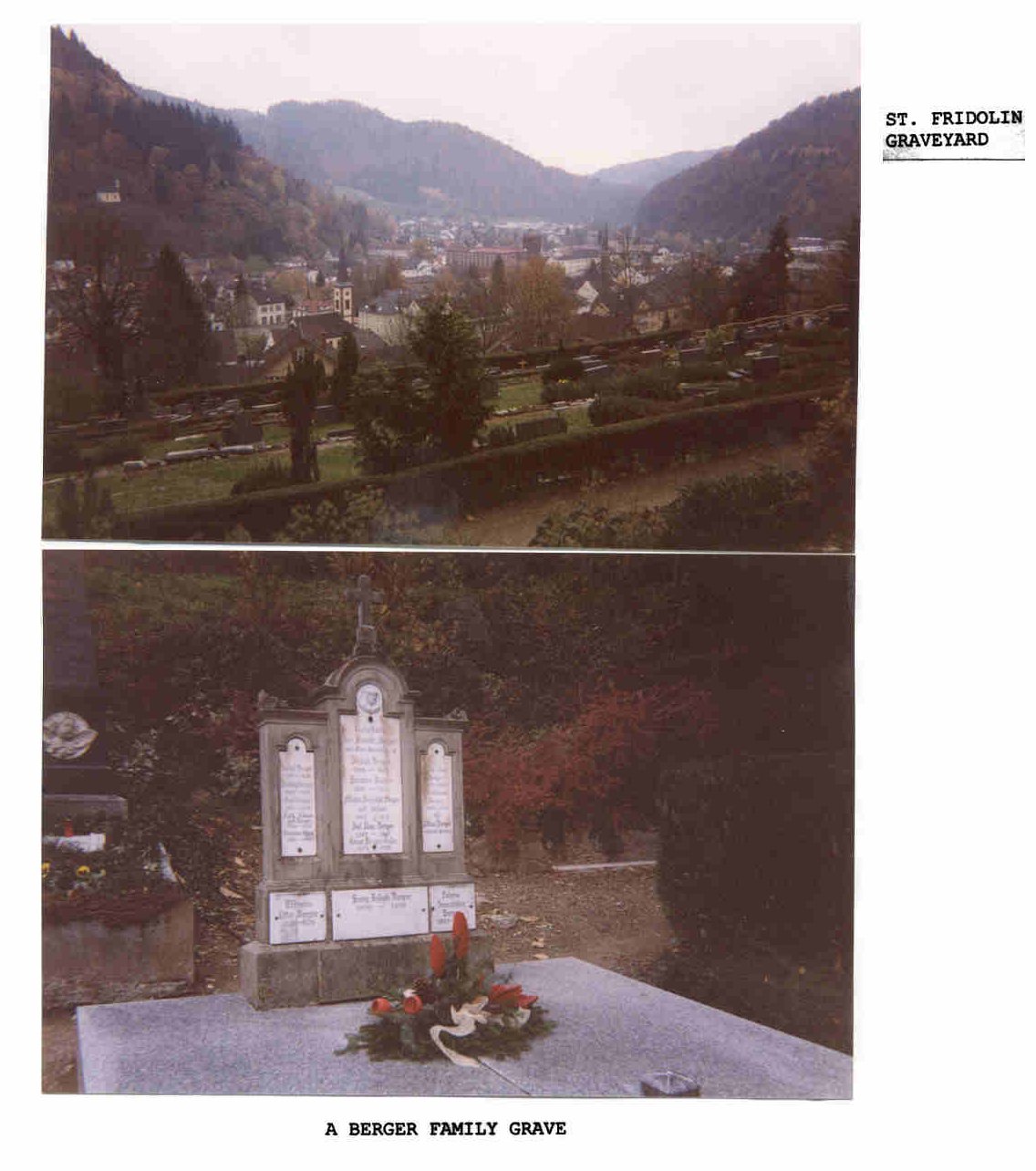

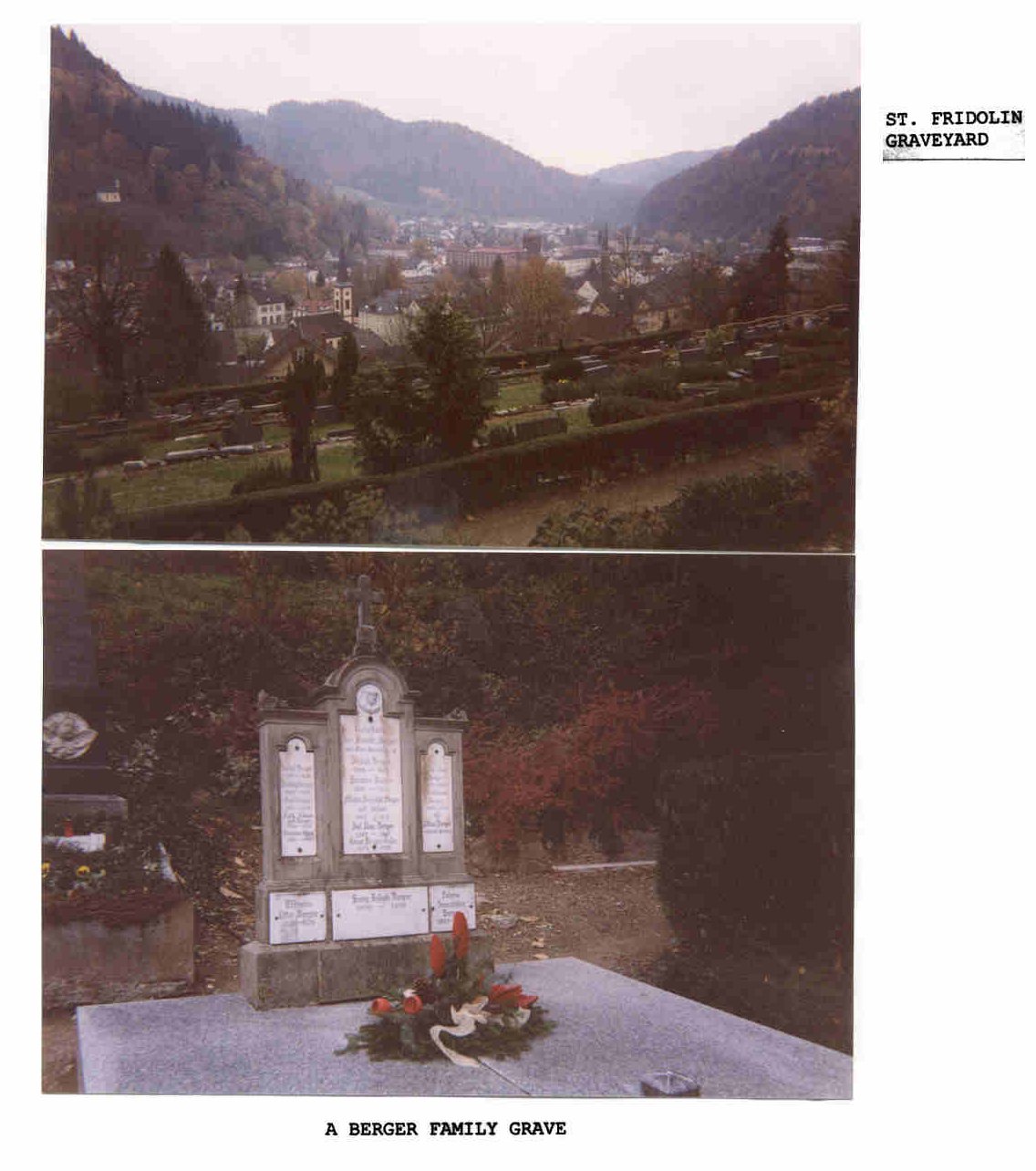

Seeing no graveyard, I rang the rectory doorbell, and was answered

by the priest and housekeeper together. I introduced myself, told them I

was a Berger and my ancestors had come from here 150 years ago. A

non-commital nod to that. Again, too many Bergers I suppose, but the

pastor was quite friendly. We had only a short conversation because he

spoke no English. I asked directions to the parish graveyard, which in

this case was not contiguous with the church. He directed me to a steep

hillside site up the road, where I found the same well kept and

sumptuous gravesites, and lots of Bergers, but no Trefzgers. St. Fridolin

had only a generalized monument to the dead of the two world wars, but

I saw many familiar inscribed on the tombstones: Johann Berger, Joseph

Berger, Anna Berger, Teresa Berger, Amanda and Alfred Berger were

all there.

Our ancestors left Germany shortly after the failed revolutions of

1848, when there were uprisings of the common people allover Europe

trying to throw off the yoke of the nobility and challenging the divine

right of Kings. Dire retribution followed, and perhaps our ancestors left

to avoid the worst of its consequences. They were in good, or at least

famous, company. That same year Karl Marx was driven out of Basel,

says my travel guide, just a few miles to the southwest of these remote

valleys, and wound up in London writing the Communist Manifesto in

the British Museum. I am not sure if the Bergers and Trefzgers were

driven more by political or economic motives, maybe a combination of

the two. But leave they did, and as a result, our Johanns, AIfreds,

Friedrichs, Annas, Theresas, Josephs, and all the rest found a very

different future than those with the same names that lie in these

graveyards of St. Martin and St. Fridolin

Return to: 1st_Page Trefzger Roots Berger Roots